In the long run my observations have convinced me that some men, reasoning preposterously, first establish some conclusion in their minds which, either because of its being their own or because of their having received it from some person who has their entire confidence, impresses them so deeply that one finds it impossible ever to get it out of their heads. Such arguments in support of their fixed idea as they hit upon themselves or hear set forth by others, no matter how simple and stupid these may be, gain their instant acceptance and applause. On the other hand whatever is brought forward against it, however ingenious and conclusive, they receive with disdain or with hot rage — if indeed it does not make them ill. Beside themselves with passion, some of them would not be backward even about scheming to suppress and silence their adversaries.

Saturday, August 31, 2013

Disdain or with hot rage

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632) by Galileo Galilei, p. 322

Friday, August 30, 2013

Rather bear those ills we have than fly to others that we know not of?

A classical rendition of the decision-maker's dilemma. From William Shakespeare's Hamlet, Act 3 scene 1, the famous soliloquy,

To be, or not to be--that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them. To die, to sleep-- No more--and by a sleep to say we end The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to. 'Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep-- To sleep--perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th' oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th' unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprise of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action. -- Soft you now, The fair Ophelia! -- Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remembered.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

The mind is slow to unlearn what it learnt early.

The Roman Stoic Seneca left us a rich portfolio of aphorisms pertaining to decision making.

Difficulties strengthen the mind, as labor does the body.

The greater part of progress is the desire to progress.

I do not distinguish by the eye, but by the mind, which is the proper judge.

I shall never be ashamed of citing a bad author if the line is good.

If a man does not know to what port he is steering, no wind is favorable to him.

It is a great thing to know the season for speech and the season for silence.

It is a youthful failing to be unable to control one's impulses.

It is easier to exclude harmful passions than to rule them, and to deny them admittance than to control them after they have been admitted.

It is rash to condemn where you are ignorant.

Speech is the mirror of the mind. (Imago Animi Sermo Est)

The arts are the servant; wisdom its master.

The first step towards amendment is the recognition of error.

The mind is slow to unlearn what it learnt early.

The path of precept is long, that of example short and effectual.

We most often go astray on a well trodden and much frequented road.

Where reason fails, time oft has worked a cure.

Where the speech is corrupted, the mind is also.

The best ideas are common property.

Nothing is as certain as that the vices of leisure are gotten rid of by being busy.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

If you want Wal-Mart to have a labor force like Trader Joe’s and Costco, you probably want them to have a business model like Trader Joe’s and Costco

From Why Wal-Mart Will Never Pay Like Costco by Megan McArdle.

In other words, Trader Joe’s and Costco are the specialty grocer and warehouse club for an affluent, educated college demographic. They woo this crowd with a stripped-down array of high quality stock-keeping units, and high-quality customer service. The high wages produce the high levels of customer service, and the small number of products are what allow them to pay the high wages. Fewer products to handle (and restock) lowers the labor intensity of your operation. In the case of Trader Joe’s, it also dramatically decreases the amount of space you need for your supermarket ... which in turn is why their revenue per square foot is so high. (Costco solves this problem by leaving the stuff on pallets, so that you can be your own stockboy).

Both these strategies work in part because very few people expect to do all their shopping at Trader Joe’s, and no one expects to do all their shopping at Costco. They don’t need to be comprehensive. Supermarkets, and Wal-Mart, have to devote a lot of shelf space, and labor, to products that don’t turn over that often.

Wal-Mart’s customers expect a very broad array of goods, because they’re a department store, not a specialty retailer; lots of people rely on Wal-Mart for their regular weekly shopping. The retailer has tried to cut the number of SKUs it carries, but ended up having to put them back, because it cost them in complaints, and sales. That means more labor, and lower profits per square foot. It also means that when you ask a clerk where something is, he’s likely to have no idea, because no person could master 108,000 SKUs. Even if Wal-Mart did pay a higher wage, you wouldn’t get the kind of easy, effortless service that you do at Trader Joe’s because the business models are just too different. If your business model inherently requires a lot of low-skill labor, efficiency wages don’t necessarily make financial sense.

That’s not the only reason that the Trader Joe’s/Costco model wouldn’t work for Wal-Mart. For one thing, it’s no accident that the high-wage favorites cited by activists tend to serve the affluent; lower income households can’t afford to pay extra for top-notch service. If it really matters to you whether you pay 50 cents a loaf less for generic bread, you’re not going to go to the specialty store where the organic produce is super-cheap and the clerk gave a cookie to your kid. Every time I write about Wal-Mart (or McDonald's, or [insert store here]), several people will e-mail, or tweet, or come into the comments to say they’d be happy to pay 25 percent more for their Big Mac or their Wal-Mart goods if it means that the workers are well paid. I have taken to asking them how often they go to Wal-Mart or McDonald's. So far, no one has reported going as often as once a week; the modal answer is a sudden disappearance from the conversation. If I had to guess, I’d estimate that most of the people making such statements go to Wal-Mart or McDonald's only on road trips.

However, there are people for whom the McDonald's Dollar Menu is a bit of a splurge, and Wal-Mart’s prices mean an extra pair of shoes for the kids. Those people might theoretically favor high wages, but they do not act on those beliefs -- just witness last Thanksgiving’s union action against Wal-Mart, which featured indifferent crowds streaming past a handful of activists, most of whom did not actually work for Wal-Mart.

If you want Wal-Mart to have a labor force like Trader Joe’s and Costco, you probably want them to have a business model like Trader Joe’s and Costco -- which is to say that you want them to have a customer demographic like Trader Joe’s and Costco. Obviously if you belong to that demographic -- which is to say, if you’re a policy analyst, or a magazine writer -- then this sounds like a splendid idea. To Wal-Mart’s actual customer base, however, it might sound like “take your business somewhere else.”

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

There is a correct answer to that question, but it’s unlikely we’ll ever know what it was.

From Why Do Education and Health Care Cost So Much? by Megan McArdle. a great example of the challenges related to causal density. We may accurately identify all the causes of an outcome but still not be able, because of poor understanding of the relationships between root causes, to predict outcomes. Absent accurate prediction, we don't really understand the nature of a problem at all.

So how do we explain health care and college cost inflation? Well, health care economist David Cutler once offered me the following observation: In health care, as in education, the output is very important, and impossible to measure accurately. Two 65-year-olds check into two hospitals with pneumonia; one lives, one dies. Was the difference in the medical care, or their constitutions, or the bacteria that infected them? There is a correct answer to that question, but it’s unlikely we’ll ever know what it was. Similarly, two students go to different colleges; one flunks out, while the other gets a Rhodes Scholarship. Is one school better, or is one student? You can’t even answer these questions by aggregating data; better schools may attract better students. Even when you control for income and parental education, you’re left with what researchers call “omitted variable bias” -- a better school may attract more motivated and education-oriented parents to enroll their kids there. So on the one hand, we have two inelastic goods with a high perceived need; and on the other hand, you have no way to measure quality of output. The result is that we keep increasing the inputs: the expensive professors and doctors and research and facilities.I would quibble with McArdle. There are actually two problems. It is true that it is hard to measure education and health outcomes and that is a challenge. But even if we were able to measure with great precision and accuracy, that is still not the same as forecasting. Measuring is a predicate to forecasting. If we precisely and accurately measure our initiating action X, we want to know with some level of accuracy and certainty that X will lead to Y, the outcome we desire. If we cannot predict the outcome, it means we don't understand the relationship between and among the various causes.

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult.

Aphorisms by Hippocrates, the very first aphorism:

The Latin original is Vita brevis, ars longa, occasio praeceps, experimentum periculosum, iudicium difficile.

Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.A neat summation that remains true in virtually all fields today. It takes a long time to develop skills (Art long) compared to the allotted time we have to develop those skills (life is short), the pace of change is fast and we only have one chance to get it right (the crisis fleeting), the consequences are great (experience perilous) and as always the "decision difficult." The second sentence is not perhaps as crisp but is just as consequential. A good decision without support from all parties in the context (the patient, the attendants, and externals) is like as not to fail. The challenge is that in the modern era, rarely can we "make" others cooperate, rather we have to convince, motivate, or incent them to cooperate, an endeavor fraught with variable outcomes. A variability that is less and less desirable, the greater the consequences arising from the decision.

The Latin original is Vita brevis, ars longa, occasio praeceps, experimentum periculosum, iudicium difficile.

Friday, August 23, 2013

Most frequent errors, fallacies, and biases when decision-making

Looking for something that might tell me how often logical fallacies and cognitive biases occur in discussions, I could find nothing at all. Not willing to let go, I resorted to using N-grams. It has the drawback that some fallacies and biases are terms commonly used in other contexts (ex: false memory) or returned no results (ex: normalcy bias). I lost about hundred biases and fallacies from this weakness, though generally more obscure or nuanced biases and fallacies. This was about half the population. Of the remaining hundred or so, I was able to obtain an N-gram number and then rank from largest to smallest.

All this tells us is the degree to which specific biases, errors and fallacies are being discussed in books. I am making the bold inference that specific biases and fallacies which are discussed frequently are correspondingly more common or more problematic (i.e. perhaps they don't occur that often but are more consequential when they do). So having caveated the corpus to death, I present the top most commonly discussed biases and fallacies in a whispering ghost of a list.

These would seem to be the errors, fallacies, and biases you are most likely to encounter when working with a group to reach an empirical, logical, and evidence based decision.

All this tells us is the degree to which specific biases, errors and fallacies are being discussed in books. I am making the bold inference that specific biases and fallacies which are discussed frequently are correspondingly more common or more problematic (i.e. perhaps they don't occur that often but are more consequential when they do). So having caveated the corpus to death, I present the top most commonly discussed biases and fallacies in a whispering ghost of a list.

These would seem to be the errors, fallacies, and biases you are most likely to encounter when working with a group to reach an empirical, logical, and evidence based decision.

Trade-offsNot quite the list or order I would have expected, but not completely out of the realm of probability. The top ten in particular are broadly consistent with my experience in terms of mistakes teams make when trying to arrive at decisions.

Anecdotal Evidence

False assumptions

Cognitive Dissonance

Anthropomorphism

Fallacy of composition

Unstated Assumptions

Slippery Slope

Selective perception

Halo effect

Argumentum Ad hominem

Illusory correlation

Source Credibility

Forer effect (aka Barnum effect)

Sunk cost bias

Begging the Question

Fundamental attribution error

Generalizing personalities

Amphiboly

Hindsight bias

Solution to low public transportation utilization

From Mobility for the Poor: Car-Sharing, Car Loans, and the Limits of Public Transit by Jeff Khau. An example of the importance of establishing the difference between correlation and causation; of the importance of directionality of causation; of context; of root cause analysis; and goal definition.

Theoretically, one can look at this graph and legitimately make the argument that in order to increase public utilization of public transportation, one ought to increase the average commute time. It is a good exercise in critical thinking to spot the fallacy of such an interpretation.

Theoretically, one can look at this graph and legitimately make the argument that in order to increase public utilization of public transportation, one ought to increase the average commute time. It is a good exercise in critical thinking to spot the fallacy of such an interpretation.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Precision and Accuracy

While it might seem an exercise in splitting hairs, in Approximate quotations by Mark Liberman, the author opens up the basis for a good discussion on the differences between approximation, precision and accuracy. All three aspects are important and necessary but they are different and are each more appropriate in different contexts.

An approximate quote can yield a better general sense of what was being communicated but then the accuracy depends on the interpretation of the journalist. A direct quote as from a transcript is more precise but more burdensome to the reader.

Sometimes the need for precision is paramount. On other occasions, an approximation is more efficient. It is a matter of horses for courses, as long as we keep the distinction between precision and accuracy clear.

An approximate quote can yield a better general sense of what was being communicated but then the accuracy depends on the interpretation of the journalist. A direct quote as from a transcript is more precise but more burdensome to the reader.

Sometimes the need for precision is paramount. On other occasions, an approximation is more efficient. It is a matter of horses for courses, as long as we keep the distinction between precision and accuracy clear.

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Fairy tales masquerading as evidence

Science bible stories, take 27 by Mark Liberman is a useful discussion (including in the comments) about the tendency of media to take up a topical research paper without regard to the methodological robustness of the study or whether the results are meaningfully true.

RELATED: The culturomic psychology of urbanization by Mark Liberman

As I observed a few years ago, "scientific studies" have taken over the place that bible stories used to occupy. It's only fundamentalists like me who worry about whether they're true. For most people, it's enough that they can be interpreted to be morally instructive.[snip]

I'd add a third important factor: by and large, the "wise men" (and now the "wise women") don't really care about whether the empirical and theoretical foundations of their opinions are sound . They care about readers, ratings, and reputation — and in some cases about political outcomes or cultural values — with truth relevant only insofar as it affects those goals.I think Liberman is correct. People rarely consider what evidence they need in order to make an argument, instead they go after information that is convenient to get. At the same time, the market structure for ideas and information is such that there are incentives to produce affirming information to a range of prejudices, regardless of the truth of the matter. Elsewhere I refer to this as cognitive pollution as it constitutes dirt in the system that tends to occlude rather than clarify.

RELATED: The culturomic psychology of urbanization by Mark Liberman

Monday, August 19, 2013

To analyze does not necessarily mean to produce useful information

From Reviewing the Movies: Audiences vs. Critics by Catherine Rampell.

It is a fair and interesting question or set of questions. Do audiences and critics assess movies in different ways? If so, in what ways do they differ? Which views, audience or critics, provide a better forecast of future performance? These questions apply to art, sports, books, etc. There are answers to some of these questions. The general informed public and specialists do tend to review things differently. General informed public tend to factor in more context and larger macro considerations than do specialists. General informed public tend to be better forecasters than are specialists. Nate Silver covers a lot of this in his The Signal and The Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail - but Some Don't

What is notable is that Rampell asks a legitimate question and has an idea on how to answer the question. Her error is to use information that is available (Rotten Tomatoes Database) rather than information that is needed. There is a fairly detailed critique of her analysis in the comments. The article serves as an example of Selection Bias (the distortion of a statistical analysis, resulting from the method of collecting samples) and Information Bias (the tendency to seek information even when it cannot affect action), and possible Mere Exposure Bias (the tendency to express undue liking for things merely because of familiarity with them).

It is a fair and interesting question or set of questions. Do audiences and critics assess movies in different ways? If so, in what ways do they differ? Which views, audience or critics, provide a better forecast of future performance? These questions apply to art, sports, books, etc. There are answers to some of these questions. The general informed public and specialists do tend to review things differently. General informed public tend to factor in more context and larger macro considerations than do specialists. General informed public tend to be better forecasters than are specialists. Nate Silver covers a lot of this in his The Signal and The Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail - but Some Don't

What is notable is that Rampell asks a legitimate question and has an idea on how to answer the question. Her error is to use information that is available (Rotten Tomatoes Database) rather than information that is needed. There is a fairly detailed critique of her analysis in the comments. The article serves as an example of Selection Bias (the distortion of a statistical analysis, resulting from the method of collecting samples) and Information Bias (the tendency to seek information even when it cannot affect action), and possible Mere Exposure Bias (the tendency to express undue liking for things merely because of familiarity with them).

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Almost all Americans devoutly believe, the liberal, market principles on which our country is built will triumph around the world.

From Bambi Meets Godzilla In The Middle East by Walter Russell Mead. Read the whole thing.

The end of history, which AI founder Francis Fukuyama used to describe the historical implications of the Cold War, is to American political philosophy what the Second Coming is to Christians. In the end, almost all Americans devoutly believe, the liberal, market principles on which our country is built will triumph around the world. Asia, Africa, South America, the Middle East and even Russia will some day become democratic societies with market economies softened by welfare states and social safety nets. As a nation, we believe that democracy is both morally better and more practical than other forms of government, and that a regulated market economy offers the only long term path to national prosperity. As democracy and capitalism spread their wonder-working wings across the world, peace will descend on suffering humanity and history as we’ve known it will be at an end.[snip]

It seems misanthropic to doubt that a particular country isn’t on the road to freedom and prosperity, and it also seems like heresy against our national creed. That tendency is reinforced among our policy elite and chattering classes. The “experts” ought to know better and be more skeptical, but they are often more naive and more dogmatic than the American people at large. It is often the best educated and connected who are most confident, for example, that political science maxims work better than historical knowledge and reflection when it comes to analyzing events and predicting developments. When democratic peace theory or some other beautiful intellectual system (backed with regressions and statistically significant correlations in all their austere beauty) adds its weight to the national political religion, a reasonable faith can morph into blind zeal. Bad things often follow.[snip]

What Americans often miss is that while democratic liberal capitalism may be where humanity is heading, not everybody is going to get there tomorrow. This is not simply because some leaders selfishly seek their own power or because evil ideologies take root in unhappy lands. It is also because while liberal capitalist democracy may well be the best way to order human societies from an abstract point of view, not every human society is ready and able to do walk that road now. Some aren’t ready because like Haiti they face such crippling problems that having a government, any government, that effectively enforces the law and provides basic services across the country is beyond their grasp. Some aren’t ready because religious or ethnic tensions would rip a particular country apart and cause civil war. Some aren’t ready because the gap between the values, social structures and culture of a particular society make various aspects of liberal capitalism either distasteful or impractical. In many places, the fact that liberal democratic capitalism is historically associated with western imperialism and arrogance has poisoned the well. People simply do not believe that this foreign system will work for them, and they blame many of the problems they face on the countries in Europe and North America who so loudly proclaim the superiority of a system they feel has victimized them.

Americans need to face an unpleasant fact: while American values may be the answer long term to the Middle East’s problems, they are largely irrelevant to much that is happening there now. We are not going to stop terrorism, at least not in the short or middle term, by building prosperous democratic societies in the Middle East. We can’t fix Pakistan, we can’t fix Egypt, we can’t fix Iraq, we can’t fix Saudi Arabia and we can’t fix Syria. Not even the people who live in those countries can fix them at this point; what has gone wrong is so deeply rooted and so multifaceted that nothing anybody can do will turn them into good candidates for membership in the European Union anytime soon. If we could turn Pakistan into Denmark, the terrorists there would probably settle down—but that isn’t going to happen on any policy-relevant timetable. We must deal with terrorism (and our other interests in the region) in a world in which the basic conditions that breed terrorists aren’t going away.

Friday, August 16, 2013

All this should challenge the application of the antismoking model to obesity.

In The Making of the Obesity Epidemic: How Food Activism Led Public Health Astray by Helen Lee, the author makes the argument that the nature of obesity is misunderstood, that the evidence of the ill-effects of obesity are poorly understood, and that public policy has been ineffective. In addition, the author makes the claim that significant part of policy ineffectiveness arises because the public health community mistook the lessons of the campaign against smoking and attempted to apply the same approaches in the smoking campaign to the campaign against obesity, expecting similar results when in fact the two issues were different and the approaches to one could not be extrapolated to the other.

All this should challenge the application of the antismoking model to obesity. Where smoking can be banned, overeating cannot be. The two behaviors are similar only in that they, like much else we do, are factors in health. There is no secondhand eating. Nor can there be “no overeating” sections of restaurants and airplanes. Overeating and unhealthy foods are fuzzily, subjectively, and variously defined, whereas we can all agree on what smoking and cigarettes are. What that means is that unhealthy foods will remain widely available — even more available than cigarettes, which can still be found at any corner store. If history is any guide, food availability and diversity are likely to increase, not decrease.

Monday, August 12, 2013

On the importance of clarity

Journalistic train wreck

S. Dakota Indian Foster Care 1: Investigative Storytelling Gone Awry by Edward Schumacher-Matos

A year long investigation led to a three part radio series with serious allegations of moral, financial and legal malfeasance. The ombudsman of the news organization, NPR, then spent a year and a half investigating allegations that the substantial majority of the news report was misleading and factually incorrect. As with any major dust-up there are points and counter-points. It appears though that, on balance, the ombudsman is right, that the report departed from the organization's own journalistic standards and ethics in material ways.

It is worth reading to reinforce 1) that there are always two perspectives (or more), 2) that even reporting from organizations with resources and a reputation for integrity can be dramatically wrong, 3) that misplaced and unquestioned assumptions were likely a material contributor to a journalistic train wreck, 4) that a compelling narrative arc is no substitute for factual accuracy, 5) that context is critical, and 6) journalistic accolades and awards can go to reports that are materially wrong.

A year long investigation led to a three part radio series with serious allegations of moral, financial and legal malfeasance. The ombudsman of the news organization, NPR, then spent a year and a half investigating allegations that the substantial majority of the news report was misleading and factually incorrect. As with any major dust-up there are points and counter-points. It appears though that, on balance, the ombudsman is right, that the report departed from the organization's own journalistic standards and ethics in material ways.

It is worth reading to reinforce 1) that there are always two perspectives (or more), 2) that even reporting from organizations with resources and a reputation for integrity can be dramatically wrong, 3) that misplaced and unquestioned assumptions were likely a material contributor to a journalistic train wreck, 4) that a compelling narrative arc is no substitute for factual accuracy, 5) that context is critical, and 6) journalistic accolades and awards can go to reports that are materially wrong.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

I ought to have eaten a pretzel in the first place!

From Fables and Fairy Tales by Leo Tolstoy, page 37. An example of the logical fallacy post hoc ergo propter hoc, combined with the availability heuristic.

Three Rolls a PretzelTaking the last link in the chain of events and stopping there invites misdiagnosis of a situation. It is not uncommon that a team will seize on the most recent cause as the most obvious cause, will already be halfway towards solving the problem ("Always stick with pretzels") and won't want to go back and look at root causes.

Feeling hungry one day, a peasant bought himself a large roll and ate it. But he was still hungry, so he bought another roll and ate it. Still hungry he bought a third roll and ate it. When the three rolls failed to satisfy his hunger, he bought some pretzels. After eating one pretzel he no longer felt hungry.

Suddenly he clapped his hand to his head and cried: "What a fool I am! Why did I waste all those rolls? I ought to have eaten a pretzel in the first place!"

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

Sharing the decision

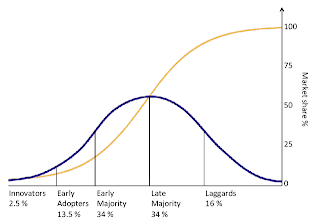

Diffusion of Innovations by Everett Rogers.

Originator of the term early adopters, Rogers laid the foundation for much contemporary work on the diffusion of ideas. His model remains in wide circulation.

Originator of the term early adopters, Rogers laid the foundation for much contemporary work on the diffusion of ideas. His model remains in wide circulation.

Good ideas can't necessarily survive on their own

Slow Ideas: Some innovations spread fast. How do you speed the ones that don’t? by Atul Gawande

The capacity to create and innovate is integral to effective decision-making. Thinking imaginatively from multiple perspectives is part of the challenge. But once an idea is out there and proven, there is still the issue of uptake. A good idea which is not accepted is not worth much. Many consider this to be a simple matter of communication, or creating the right reward (and punishment) incentives. Some dismiss the issue entirely on the grounds that if the idea is worthwhile, it will be adopted anyway.

It's not quite that simple as Gawande points out. He points to the contrasting fates of anesthesia and hospital hygiene.

The use of anesthesia spread like lightening.

The capacity to create and innovate is integral to effective decision-making. Thinking imaginatively from multiple perspectives is part of the challenge. But once an idea is out there and proven, there is still the issue of uptake. A good idea which is not accepted is not worth much. Many consider this to be a simple matter of communication, or creating the right reward (and punishment) incentives. Some dismiss the issue entirely on the grounds that if the idea is worthwhile, it will be adopted anyway.

It's not quite that simple as Gawande points out. He points to the contrasting fates of anesthesia and hospital hygiene.

The use of anesthesia spread like lightening.

On October 16, 1846, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Morton administered his gas through an inhaler in the mouth of a young man undergoing the excision of a tumor in his jaw. The patient only muttered to himself in a semi-conscious state during the procedure. The following day, the gas left a woman, undergoing surgery to cut a large tumor from her upper arm, completely silent and motionless. When she woke, she said she had experienced nothing at all.In contrast,

Four weeks later, on November 18th, Bigelow published his report on the discovery of “insensibility produced by inhalation” in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. Morton would not divulge the composition of the gas, which he called Letheon, because he had applied for a patent. But Bigelow reported that he smelled ether in it (ether was used as an ingredient in certain medical preparations), and that seems to have been enough. The idea spread like a contagion, travelling through letters, meetings, and periodicals. By mid-December, surgeons were administering ether to patients in Paris and London. By February, anesthesia had been used in almost all the capitals of Europe, and by June in most regions of the world.

There were forces of resistance, to be sure. Some people criticized anesthesia as a “needless luxury”; clergymen deplored its use to reduce pain during childbirth as a frustration of the Almighty’s designs. James Miller, a nineteenth-century Scottish surgeon who chronicled the advent of anesthesia, observed the opposition of elderly surgeons: “They closed their ears, shut their eyes, and folded their hands. . . . They had quite made up their minds that pain was a necessary evil, and must be endured.” Yet soon even the obstructors, “with a run, mounted behind—hurrahing and shouting with the best.” Within seven years, virtually every hospital in America and Britain had adopted the new discovery.

Sepsis—infection—was the other great scourge of surgery. It was the single biggest killer of surgical patients, claiming as many as half of those who underwent major operations, such as a repair of an open fracture or the amputation of a limb. Infection was so prevalent that suppuration—the discharge of pus from a surgical wound—was thought to be a necessary part of healing.The key conclusion?

In the eighteen-sixties, the Edinburgh surgeon Joseph Lister read a paper by Louis Pasteur laying out his evidence that spoiling and fermentation were the consequence of microorganisms. Lister became convinced that the same process accounted for wound sepsis. Pasteur had observed that, besides filtration and the application of heat, exposure to certain chemicals could eliminate germs. Lister had read about the city of Carlisle’s success in using a small amount of carbolic acid to eliminate the odor of sewage, and reasoned that it was destroying germs. Maybe it could do the same in surgery.

During the next few years, he perfected ways to use carbolic acid for cleansing hands and wounds and destroying any germs that might enter the operating field. The result was strikingly lower rates of sepsis and death. You would have thought that, when he published his observations in a groundbreaking series of reports in The Lancet, in 1867, his antiseptic method would have spread as rapidly as anesthesia.

Far from it. The surgeon J. M. T. Finney recalled that, when he was a trainee at Massachusetts General Hospital two decades later, hand washing was still perfunctory. Surgeons soaked their instruments in carbolic acid, but they continued to operate in black frock coats stiffened with the blood and viscera of previous operations—the badge of a busy practice. Instead of using fresh gauze as sponges, they reused sea sponges without sterilizing them. It was a generation before Lister’s recommendations became routine and the next steps were taken toward the modern standard of asepsis—that is, entirely excluding germs from the surgical field, using heat-sterilized instruments and surgical teams clad in sterile gowns and gloves.

But technology and incentive programs are not enough. “Diffusion is essentially a social process through which people talking to people spread an innovation,” wrote Everett Rogers, the great scholar of how new ideas are communicated and spread. Mass media can introduce a new idea to people. But, Rogers showed, people follow the lead of other people they know and trust when they decide whether to take it up. Every change requires effort, and the decision to make that effort is a social process.Read the whole thing.

This is something that salespeople understand well. I once asked a pharmaceutical rep how he persuaded doctors—who are notoriously stubborn—to adopt a new medicine. Evidence is not remotely enough, he said, however strong a case you may have. You must also apply “the rule of seven touches.” Personally “touch” the doctors seven times, and they will come to know you; if they know you, they might trust you; and, if they trust you, they will change.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)